In his seminal High Output Management, the late Andy Grove defines “leverage” as the measure of output generated by a given managerial activity. He provides the following formula,

managerial output = output of organization = L1 x A1 + L2 x A2 + L3 x A3…

where L is the leverage of the activity and A is the activity itself. As a manager, your job is to maximize the output of your team and those in your sphere of influence, and the most effective way to do that is to prioritize high leverage activities.

High-Leverage Activities

To effectively prioritize high-leverage activities over low-leverage activities, the first step is knowing how to identify which activities are which. According to Grove, high-leverage activities are achieved when:

Many people are affected by one manager

A person’s activity or behavior over a long period of time is affected by a manager’s brief, well-focused set of words or actions

A large group’s work is affected by an individual supplying a unique, key piece of knowledge or information

Examples of high-leverage activities include one-on-ones; coaching and development; projects that align with organizational objectives; and meetings with clear, actionable outcomes and decisions. High-leverage activities are force multipliers: the input provided (e.g., from a well-structured team meeting, a 1:1, or knowledge sharing) results in more output than the direct input provides, or, as Grove puts it, “An activity with high leverage will generate a high level of output.” Think about high-leverage activities like the ripples created when you drop a pebble in water. The activity is the pebble, and the further the ripples go, the more leverage the activity has.

Once you’ve determined what your high-leverage work is, you can further amplify your output by moving it to your high-energy times of the day. More on this in a moment.

Low-Leverage Activities

Alas, if there are high-leverage activities, it stands to reason that there are low-leverage activities, too. Low-leverage activities are best described as activities where the input and output are one to one. Low-leverage activities are achieved when:

Working in isolation

Work has low business value

Ineffectively delegating

Ineffectively managing time

Examples of low-leverage activities include working to solve a problem on your own because you fail to delegate to your team; focusing on a project that isn’t aligned with the broader objectives of the organization; or attending meetings that include redundant representation (i.e., other managers or members on your team that can knowledge transfer to a number of individuals after) or have no agenda to help you determine whether you are required to attend. If you, as a manager, find yourself doing low-leverage work, your first step is to determine if you’re the one who should be doing it. More than likely, it should be delegated to someone on your team.

Another example you may be familiar with is attending a meeting that includes multiple managers in the same organization. Here’s the “expensive meeting” calculation: Say three managers each have an annual salary of $100,000 (we’ll take some liberties to round their hourly pay to $50). If there are three meetings per week that all three attend, and each meeting is an hour long, that’s a whopping $1800 per month in combined manager time spent in those meetings, or close to the cost of a 40-hour week of a single manager’s time. A single manager spending one week per month attending a meeting with redundant representation is a low-leverage endeavor. Sometimes, low-leverage work is unavoidable (for example, some meetings require the presence of multiple managers in the same org). If that’s the case, then de-prioritize it and move it to a low-energy time of day.

Negative-Leverage Activities

Finally, at the far end of the spectrum are negative-leverage activities. Negative-leverage activities are achieved:

When decisions are delayed, put off, or never made

When friction is introduced into the decision-making process

Abdication, or when no follow-through is committed after delegation

Examples of negative-leverage activities include being unprepared for meetings; meetings without actionable follow-up items or clear decisions (or meetings to schedule other meetings); or failing to follow up on tasks you’ve delegated to your team. If you find yourself in negative-leverage territory, the best thing you can do is identify which of your behaviors are contributing and stop them, or extricate yourself from the situation as quickly as you can. You can, however, use a high-leverage tactic and provide coaching, development, or feedback to those you observe in negative- or low-leverage territory. If you’re interested in that pursuit, check out my presentation on giving effective feedback, available on jeffstrauss.net/bootcamp.

Time Management

Once you know what a high-, low-, or negative-leverage task looks like, the next step is determining how you prioritize it (although if you see negative-leverage tasks in your priorities, you’ve may want to recalibrate). Time management is a high-leverage activity, and the results derived from high-leverage activities are largely correlated with performance at every level of the organization, from entry level to senior executive. You can determine how much of your time you’re devoting to your high- and low-leverage activities by conducting a time audit.

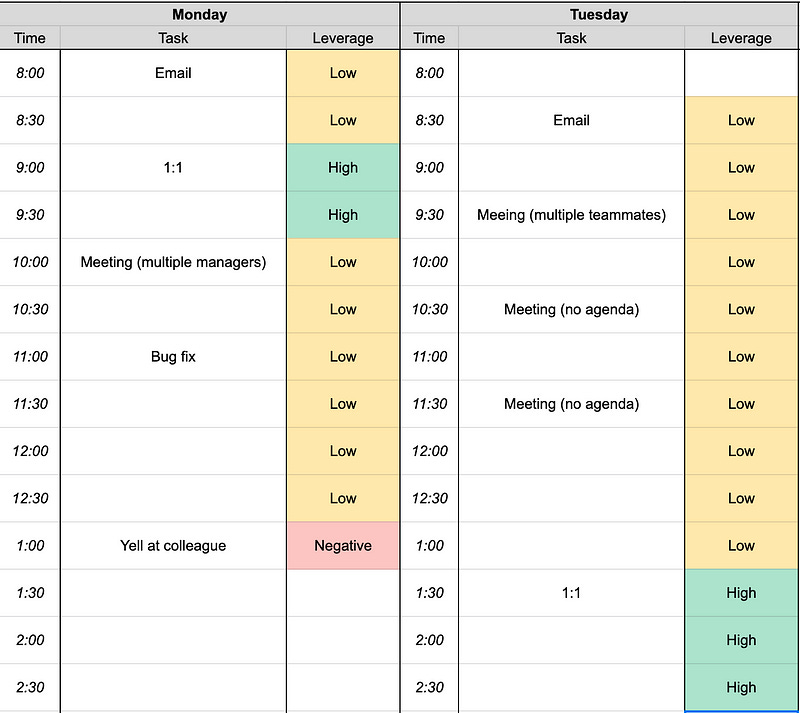

A time audit isn’t easy. It takes dedication and diligence. At a very basic level, a time audit is tracking the start and duration of an activity. You can create a spreadsheet with a heading for the day and a few columns for the time, task, and leverage, like this:

Once you have a data set for how you’re spending your time, you can start to prioritize your high-leverage activities for when you’re most engaged at work. As you become accustomed to thinking about activities as high-, low-, or negative-leverage, you’ll be able to recognize them almost by instinct and prioritize them to take advantage of when you’re best suited to accomplish them. (Here’s a deep dive on time management, if you’re interested.)

To bring this back to practicality, one example of a low-leverage activity is checking and responding to email right away. It requires context switching, can be time-consuming, and email doesn’t necessarily require a rapid response (more effective tools for that are Slack or Teams, though I still like to say that those tools are instant message, not instant respond). I’m a morning person, so I moved reviewing my email to later in the day after I’ve focused my most energized time on my high-leverage tasks, which typically include my 1:1s, team syncs, leadership meetings, or project check-ins, all scheduled for morning and early afternoon.

Final Thoughts

Leverage is a tremendously powerful management concept that’s often overlooked in the milieu of daily activities. If you’re able to prioritize your activities effectively - and coach those you lead to do the same - you’ll see the results in improved performance and outcomes.